No Products in the Cart

Tattoos are wearable art for some. For others, they signify a way of living and belonging. Likewise, they can be a representation of a person or a significant time in a person’s life. Tattoos can signal allegiances to social groups where one must earn such markings by virtue of living a particular lifestyle. We explore varying connotations of tattoo art and the sense of social belonging it fosters across time and places.

Photo credit: Brett Sayles from Pexels

Photo credit: Brett Sayles from Pexels

Body art is a practice that for centuries existed in different communities and cultures around the world. Tattoos became the most widely popularized part of that culture due to their appearance and relative ease of creation. This involves inserting ink and colour pigments via a needle into the dermis layer of the skin. As the accompanying wound heals, the design becomes permanent under the new layer of skin.

Tattoos were traditionally done manually by puncturing the skin with a needle and injecting the ink by hand. However, modern tattooing requires tattoo artists to use tattoo machines, where machines power the needles up and down to deposit ink into the skin. The procedure and accessories used in modern tattooing reduces health risks.

Dating back to the 4th millennium BC, tattoos have been a creative way to acknowledge choices, celebrate life, and pay tribute to loved ones. The art of tribal markings not only expressed a deep sacred connection to one’s kin and ancestors but also beautified the body.

Tattoo art among the Māori was a sacred marker of identity and a vehicle for storing spiritual being. Similarly, Native Americans used tattoos to represent their tribe as well as the spiritual animal or a protector attributed to them from birth. The oldest surviving tattoos were found on a mummy in the Ötz valley in the Alps named ‘Ötzi the Iceman’, dating from the 5th to 4th millennium BC.

The earliest account of tattoos in British nobility was after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, when Saxon King Harold’s mistress Edith identified his body from the tattoos on his chest. They read “Edith” and “England”. Subsequently, tattoos became popular among sailors in the 18th century after Captain James Cook came across the Maori people and returned with tattoos.

A specific tattoo would signify a crew member’s importance to the ship or an important milestone. For example, deckhands had a rope tattoo around the wrist and a sparrow represents 5,000 nautical miles travelled. Similarly, nautical stars were believed to guide a crew safely to their destination.

Photo Credit: Charlie Wagner at work, May, 1947

Photo Credit: Charlie Wagner at work, May, 1947

Because sailors were hardly ever on the mainland, majority of people couldn’t connect to the ideas of tattoos. As a result, people continued to believe they were for people of ill will. Furthermore, some states governed by Christianity, like England, banned tattoos until around the mid 19th century.

By the mid to late 19th century, European nobility widely embraced tattoos, and some made an adventure out of it. King Edward VII travelled to Jerusalem in 1862 to receive a cross tattoo from a local master artist. His sons made the same trip 20 years later. Royalty boldly showed off tattoos in late 19th to early 20th century society. For instance, Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s mother, had a snake tattooed on her wrist. Today, tattoos are common across economic classes, sexes, and ages, often as mementos or mediums of expression.

Over the years, tattoos have had to break free from various stigmas, especially its links to criminality. Law-breakers in historical China were marked by tattooing. Romans adopted a similar practice, tattooing criminals and slaves. In the 19th century, tattoos identified released U.S. convicts, Australian convicts and British army deserters. Although the general acceptance of tattoos is on the rise in Western society, it hasn’t completely shaken off the stigma.

Tattoos in Japan

The traditional Japanese style of tattooing is called Irezumi which means ‘Insertion of ink’. This hand technique employs wooden handles and metal needles attached via a silk thread. The tattoo artist, called a Horishi, were admired figures that inspired imitation. While the word tattoo may be used in Japan, it mostly refers to non-Japanese styles of tattooing. Hanabira is another form of scarification which originated in Japan. It involves a decorative scarring of a petal on the pubic mould, as an identity symbol or for purely aesthetic reasons.

In Japan, tattoos have a strong connection to the Yakuza. Their members adorn their bodies with ornate tattoos made via Irezumi. These tattoos contain traditionally symbolic designs that tell a story about that individual and identify them with their group. Although they hold a deep significance to its wearer, they are often covered up due to societal attitudes towards tattoos. A koi fish swimming upstream may signify that an individual had to overcome great difficulties on the path to his present. For the individual, the emotional significance of his journey is far more important than the repercussions. This includes not being allowed to use public pools or onsens (hot springs). Even more, a tattoo can reduce one’s chances of getting a job.

Tattoos have played an important role in African culture. With the hot climate, people did not require full body clothing. Therefore, cultural influences, expressed using body paint, tattoos and scarification were always visible. Various tribes used specific body markings as important identity markers. The Igbo people in Nigeria gave the Ichi facial marks to men who were regarded as a noble member of the Nze na Ozo society.

Yoruba tribal marks are inscribed by cutting or burning the skin at childhood. This was a mode of identification, and without these marks, one was not considered a full member of society. Designs were specific to each tribe and carried over generations. These markings became especially significant after the slave trade was abolished, as people used these marks to reconnect with their kinsmen and find their villages. Tribal marks are now a dying practice. Colonialists, who saw the art simply as barbaric scarifications, discouraged the practice in areas they controlled.

Photo Credit: Babajide Olatunji

Photo Credit: Babajide Olatunji

Other secondary functions of tribal marks were as symbols of beauty, which the Fulani, Hausa tribe are renowned for.

Body paint is a common art form across Nigeria. Henna-based tattoos are widespread among the Hausa tribe, much like Arabs and Indians. Henna has been used since antiquity to dye skin, hair and fingernails, as well as fabrics. It gives the skin a reddish-orange-to-brown colour that lasts 2-4 weeks. For people who are just not comfortable with having a mark stay there forever, it is an alternative to permanent tattoos.

The Igbos used uli, a dye made from seeds of uli plants that stained the skin black, much like henna. Also usually practiced by women, it was applied for special occasions such as marriages, chieftaincies, and funerals. Designs would last about a week. Unlike henna, by 1970, uli lost much of its popularity.

Tattoo art made a lasting impression on haute couture when Issey Miyake presented his “Tattoo dress” in 1971. The dress was homage to Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. It was a flesh-toned garment, covered in a tattoo illustrative style that blurred the line between skin and clothes. His designs challenged the conservatism that shone a bad light on how marked bodies were perceived.

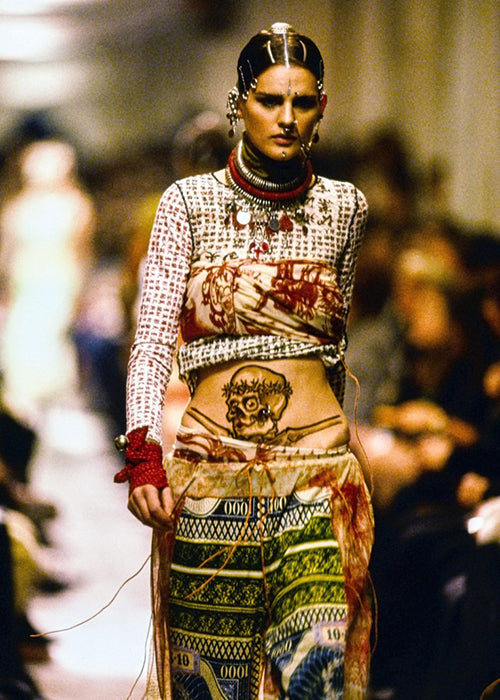

Jean-Paul Gaultier followed suit in 1994 through his “Les Tatouges” show. He used mesh clothing filled with tattoo art to mimic real tattoos. The models wore real and fake tattoos, face jewellery, and long nails. The collection certainly made a statement that various forms of self-presentation should be acceptable in fashion and society.

Fashion and the concept of body art share an intent of self-expression, but with differing characteristics of permanence. At the end of the day we may take off our clothes, or at the turn of the season, we may fancy new ones. In contrast, the expression in a tattoo remains through life and even in death.

U.Mi-1’s ‘Who am I?’ collection is a celebration of Yoruba face and body markings. The collection used appliqué on fabric to mimic the designs of tribal marks. It celebrated the sense of belonging contained in marks and tattoos as well as the creativity in each design. Unveiled at the Generation Africa show at Pitti Uomo Italy, the collection featured refugees as models, using fashion to help foster a sense of belonging in their new home.

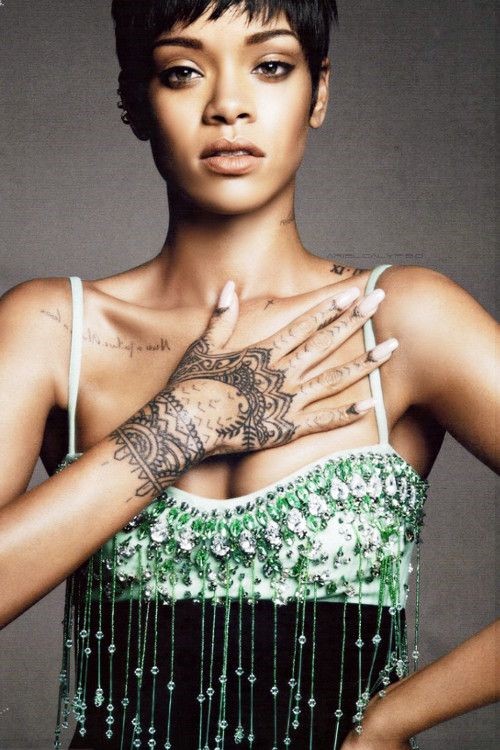

The fashion industry, celebrities and ordinary people wearing visible tattoos continue to push the envelope for modern society’s acceptance of tattoos. As the public sees different kinds of people wearing tattoos, it decimates the rigid stigma of tattoos being for criminals. Many of the presumptions and stigmas are hard to eliminate. However, we have the obligation to see differences between us as a reason to celebrate others, not denounce them.

We hope that in time people will have the freedom to beautify their body by any means they see fit, without judgment. The perception of beauty evolves constantly, and our ever-changing tastes and fashions are the best examples of it.